Hello from a place I have been only once before: the squishy and tender and paranoid months before a book I wrote is published. In this place, I’m actively grappling, I’m wrestling with my mind—with how to think about what I’ve made. I can feel the movement—the ping and the pong. I’ve made a good thing, I’ve made so many mistakes!

In this place, the novel is being offered like a little snack on a plate to early readers and reviewers, and so there is a trickle of sweet and salty feedback. For every reaction, there seems to be an equal and opposite reaction. “These characters were me.” “I couldn’t relate to any of the characters.” “The opening was too slow.” “I stayed up all night reading.” “A perfect book.” “DNFed at 7%.”

Who is right? What I am wrestling with is nothing less than the totally subjective — “relating to the way a person experiences things in his or her own mind” — nature of a single person interacting with art. How many times have I cozied up to a book that my friend raved about only to find it uninspired, uncomfortable, or offensive. Nothing is for everyone, etc. But this line of thinking comes at the question from the reader’s chair, not the writer’s, and so it is true but totally useless to me right now.

What do you do with the reactions—positive or negative, big or small—of people who have spent time with your art? Let it in to change you (make your work better, kill your faith) or lock the door to keep it out?

It was with this question in mind and in a loopy mood aided by a great and fancy little NJ dispensary that I watched the 2021 HBO documentary “Jagged” about Alanis Morissette’s 1995 album Jagged Little Pill. From jump, the film is making the case for the album’s rigor and impact. But over the course of the film, I came to see that it was also making the case that rigor and impact flow directly from belief. Talent yes. Practice, that too. Maybe some dashes of magic and timing. But mostly what Alanis had that made Jagged Little Pill great was an unshakeable belief in the integrity and value of the particular experience she was trying to render.

“I remember when I first played the record to some people and they were like, ‘it’s too in your face, it’s too urgent, it’s too emotional,’” Alanis recalls. “And I’m just like, ‘Well, I am that right now and when I’m 34 I won’t be and you won’t get another record like this.’”

Alanis made two albums that nobody remembers before she made Jagged Little Pill. She was a teeny bopper Canadian pop princess. “I had this sleazy people pleasy smiling all the time thing,” she says in the documentary, “but underneath it was just this churning of how out of integrity so much of this felt.”

She began writing songs that were angrier and sadder, songs about being objectified and sexualized in the music industry, songs about coming of age as a girl in the 1990s. A representative from her mega label, MCA, pulled her aside. “What are you doing with these new songs?” she remembers the guy saying. “You should just keep doing what you’ve been doing, what people know you as.” She declined. Her label dropped her.

“It was really painful and terrifying,” she says. “The early part of my songwriting I was working with people who said I couldn’t write. One of the liberating factors to being dropped my MCA records is that I promised myself that I would not stop until I was in the room with someone who saw me as a writer, saw me as a human being expressing herself.”

She found such a person in Glen Ballard, a producer and songwriter who had worked with artists like Michael Jackson, Paula Abdul, and Wilson Phillips. “Between February of 1994 and February of 1995,” Ballard says, of how many times he sat in a room with Alanis Morissette writing the songs that would become Jagged Little Pill. “20 separate occasions. That’s it. 20 sessions, 20 songs.”

“Most of the songs,” wrote Rachel Syme, “began as a transcription of Morissette’s interior monologue while she was living alone in Los Angeles, spending a lot of time rollerblading on the Santa Monica pier.”

Every major record company and all the secondary ones rejected the album. Finally, a 23-year-old executive at Madonna’s label, Maverick Records, was interested. “Within 30 seconds everything changed,” Oseary says. “I was already floored. I had not heard anything like it. The simplicity of the way she was able to narrate yet how complex it was at the same time.”

There are two scenes from the documentary I keep rewatching over and over again. The first is when things have begun to explode for Alanis, or “go nuclear” as one music industry insider puts it. Alanis is performing “Hand In My Pocket,” in an oversized grey t-shirt and jeans. She is holding up her curved index finger as she sings. She looks dirty. She tilts her head to the side and grinds her jaw. For much of the performance you cannot see her face, so hidden is she by her curtain of long dark hair.

“It definitely came up. Do we want to make Alanis more beautiful? Do we want to make Alanis more grungy?” the insider recounts. “What’s acceptable right now?” Apparently, Alanis did not want any of these things. Apparently, she kept wearing her baggy t-shirts. We see her bend over before the show, unclear whether she’s stretching or practicing head banging

“Hand in my pocket was the jam,” says writer and music critic Hanif Abdurraqib, interviewed in the documentary. “It’s mulling over all these contradictions. And it’s not exactly seeking and answer as much as it is seeking an affirmation that the contradictions are OK to live with.” And a few minutes later, “All the reviews of Jagged Little Pill I read were by men who could not get out of this binary of ‘Well, she’s angrier than we’d like her to be.’”

But Alanis didn’t see it that way. “When I write really angry songs about someone I’m not writing to get back at that person,” she explains. “I’m writing because it’s the only environment where I can get angry and not be destructive. It’s just an expression, unjudged, uncensored. It’s a very pure, sacred place to me.”

The second scene I keep rewatching: Alanis doing the music video for “Ironic.” She’s in the driver’s seat of a car wearing a red-pink hat, a goofy scarf and mittens. She’s beaming. She just looks so happy.

“It’s that she knows she’s the best,” I say to my partner.

“No,” they correct me gently. “It’s that she knows she has something to say.”

On the surface, the Jagged Little Pill story might seem like just another example of the world not knowing what we had when we first began to have it, of a singular artist who had the gumption to ignore the trends and critics of her time in pursuit of something timeless. Fuck the haters, in other words.

But I do not think this is what Alanis’ story means and it’s not what I mean. I’ve seen the strategy of a writer blocking out all negative feedback go very awry, especially when it comes to my students, or people in their early seasons of writing. I’ve seen students be convinced that they are doing one thing when the rest of the class and I are telling them, in no uncertain terms, that they are not in fact doing that thing, and yet the student refuses to listen. There is such a thing as study, there is such a thing as improving, as changing, as striving. There is such a thing as the fundamentals, as craft and structure and mechanics (Alanis studied and perfected these during her teeny bopper years). The best teachers can help a student see these skills and see how they work, I think. And the best workshops—often our first experiences of being reacted to and reviewed—can help a writer articulate what she cares about and why, as well as draw a kind of line of best fit through the disparate reactions, the many possible forms of the story in progress, in order to point the way towards the story’s best finished form.

I remember very clearly the day I stopped—at least partially—believing in other people’s opinions about my work. It was towards the end of my MFA degree in fiction, and I was sitting in the garden level classroom when I realized I could predict what each of my classmates and my professor were going to say about my story based on how they had reacted to my past stories. You’re going to say the characters aren’t coherent, I thought, pointing to one classmate in my mind, and you’re going to say there isn’t enough scene, I thought, thinking of another classmate, and, mentally pointing to my professor, you’re going to say you wanted more interiority. And one by one, I was right. All of these things were valid on some level, I knew. There were a million versions of the story I was writing, and some of them would satisfy her or him or my professor. And only one of them would satisfy me, and that was the only version I was now interested in. I remember having a very strong feeling then: no one else knows more about what I want to do now than I do. I was the expert on my own ambition and vision. It was a terrifying feeling, and it was the best, most freeing feeling. I couldn’t have arrived at it without serious study and reading and community, and I couldn’t have sustained it without leaving that classroom.

But Goodreads is not workshop, and Instagram is not workshop, and The New York Times Book Review is not workshop. These arenas are meant to engage with finished work, not works in progress, and they are meant to serve a different audience: readers, not writers. Read this book or don’t bother, is their supposed purpose. Books should do this not that, feel like this not that, is often their message. This book wasn’t what I thought it would be or what I wanted it to be, is the unsaid statement below much ineffective literary criticism. Many negative reviews are simply pointing towards some way in which the book supposedly failed to live up to what was promised in the marketing copy (which authors do not write!), a publishers’ well intentioned way of positioning un-positionable works of art within capitalism. It really was capitalism all along!!!

Alanis Morissette helped me see that reviews are not for me and have very little, if not nothing, to teach me about how I might have written this book better. All we can do is offer our particular experience of what we have to say in the form that feels truest to us—baggy shirt, weird scarf, and all. Looked at from this perspective, the only useful thing that negative reviews can teach us is that we didn’t go far enough in rendering the details and intensity and texture of our way of seeing something. That we could have turned the volume up even more, believed even harder, and that maybe we can, next time.

Some days I can stay inside belief and other days I can’t. On days when I can stay inside belief, it feels like the most important thing — more important than craft or skill or discipline or genius. Maybe all of the other things flow from belief, and without belief none of it is possible. Lose belief, lose everything.

Toppings

If you’re a fat person trying to get pregnant or trying to freeze your eggs, you may wish to read this piece from 2019 by

before you proceed. I wish I had!

I recently killed, in a single long drive sitting, the audiobook of Michelle Hart’s We Do What We Do in the Dark. It’s one of my favorite novels in recent memory. I found it to be deeply smart, insightful, sexy, and sad. It’s about isolation, and learning to be seen by other people, and what happens when teaching and mentoring and creative ambition get entwined with sex and physical intimacy. It does something really risky on a craft level in its middle that I’ve never seen done before and if you read it please let me know so I can talk about it with you! Plus the audio narrator did an EXCELLENT German accent.

My favorite podcast about body size, food, dieting and wellness, Maintenance Phase, has finally returned for a new episode! Run don’t walk.

I just started Stacey D’Erasmo’s work of hybrid reportage and memoir, The Long Run, which comes out in July. I’m inhaling it like medicine to help answer every creative question I’ve asked so far in this Substack. It’s about how we keep making art over the long haul of a lifetime.

Thank you to my genius designer and partner Art Phung for the new Frump Feelings logo! What an upgrade.

Book Scoop

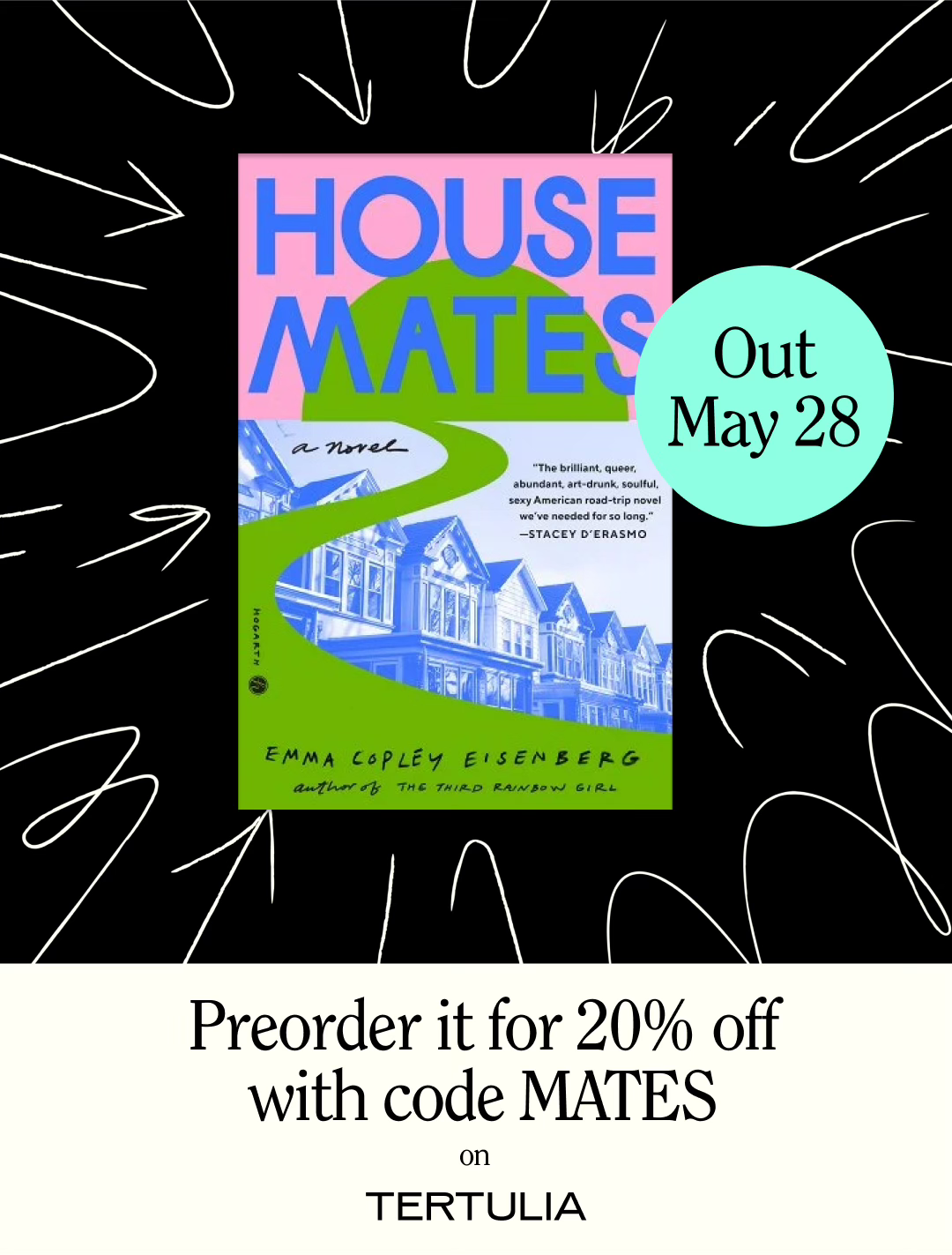

If you’ve been meaning to support Housemates, but have been put off by the price tag, the book discovery app Tertulia is currently offering 50% off preorders if you sign up for a 30-day trial, or 20% off the book with the code MATES, no strings attached.

If you want to pre-order a SIGNED copy of Housemates, have it shipped to you anywhere in the US, and support fave NYC bookstore Books Are Magic owned by

, I’m pleased to say that you can do just that now by heading over to BAM’s website.If you live in PHILADELPHIA and want to support a local bookstore, I’m thrilled to say I’m working with the good folks at Head & The Hand Books on a campaign that gets you the book plus some special Philly-related swag. Stay tuned here or follow @theheadandthehand on Instagram for more info.

happy spring forward,

Emma

Emma, this was so, so good. As a piece of writing, and as criticism about the industrial review complex.

I am excited for you, and I love your work, and I'm grateful you're sharing these parts of the journey with the rest of us.

Thanks for this perspective, Emma! And I'm keeping my eyes peeled for the Head & the Hand info -- they really are the best.