Housemates is out on Tuesday! Below is an excerpt, exclusively here on my Substack. If you’re more interested in coming to a book tour event or other news, skip to the bottom. I promise this newsletter will go back to its normal ramblings on books, culture and fat liberation soon! Thank you for staying here with me.

Excerpt from HOUSEMATES

By Emma Copley Eisenberg

The day Bernie met Leah was bright white and dying. It was a Saturday in January so the block’s many trees, roots wrecking the sidewalk as they grew, were bare, their branches lolling in the wind. There had recently been a fire at the old apple factory building that burned for days despite the best efforts of those responsible for its extinguishment, so the smell of ash still hung in the air.

They met because of the house, a three-story Victorian managed by a suburban rental company that sat on the white end of a block that marked the edge of gentrification. To the east, intrepid white queers bundled their tiny offspring into snowsuits and strapped them into all-terrain baby carriages. To the west, Black women knocked and stood in doorframes with the storm doors open, talking. To the south was the avenue, a commercial corridor that connected this neighborhood on one side to the University via expensive pizza restaurants and local pet stores and the co-op grocery store and a sprawling green park that hosted a farmer’s market and on the other side to the suburbs via Ethiopian restaurants, hair salons, and car dealerships decorated with strings of multicolored flags. To the north was the subway Bernie had taken to get here, a train that went both below and above ground, hurtling by murals that conveyed messages of love and color and caution.

Bangs combed and wearing a cheap blue blazer that was too big for her, Bernie stood in front of the house’s huge door with its great pane of glass and horizontal brass mail slot. Attached to its neighbor on one side but separated on the other by a damp alley, the house’s front garden, which sloped steeply, was a graveyard of limp frozen hostas and its porch a parking lot for bikes.

Bernie had never heard of a housing interview, but the person she’d been emailing with assured her that it was important to make sure she was “the right fit—for everybody’s sake.”

Four Swarthmore housemates, looking for a fifth, the ad read. Looking for someone with excellent emotional processing skills and ability to engage in open dialogue and proactive communication. We use a chore wheel to make sure labor is distributed equitably. Must be into Jigger the cat, most important member of the household, haha, and antiracist. Queer preferred (we all are).

Bernie rang the bell, then rapped sharply on the pane. She heard a person approach the door, then stop. In the long pause that followed, Bernie perceived the anxiety of whoever was on the other side; their hesitation palpable, their heavy breathing audible.

The door opened. Big smile, both hands waving from the wrist. Plump face framed by a haircut that seemed made for an old-fashioned hat to sit on top of it—a trapezoidal duke’s hat perhaps, in a deep color, or a round page’s cap with a feather in it. Her forehead was wet. Her name, she said, was Leah.

Come in! Leah said, then stepped back so Bernie could.

She spoke loud, so loud that it was jarring, But also winning. Bernie had never been one to make fun of those who tried very hard at life, as she herself was also such a person.

Leah leaned forward, pulled the big door closed, and locked it. They stood in the small vestibule looking at each other.

Bernie, said Bernie, pointing to herself.

I know, Leah said. I mean, I figured.

Leah shook her hair out of her eyes like a boy in a swimming pool. She was big. Big breasts atop big stomach atop thighs in men’s khaki pants, big long legs that terminated in round-toed soccer sneakers—black with white stripes. Cheeks like huge apples that shone in the weak overhead light. Nose a little pointy and downtrodden. She wore a red hoodie, the zipper of which was sliding down and revealing freckles—interesting—on her neck and chest.

Well, Leah said. Shall we?

Bernie followed Leah into the dim living room which connected to the dim dining room via a large cased opening. Light filtered in weakly through the alley side windows and several gooseneck lamps, all plugged tautly into the same outlet, made futile attempts at illumination. A shiny, exposed brick wall ran the length of the dining room and on into the fluorescent-lit kitchen, which Bernie glimpsed through a narrow door. Small bits had come unsealed from the brick wall and tumbled down onto the dark hardwood floors, which shone aggressively even in the absence of light.

The house was like a body whose blood didn’t circulate well. Energy pooled in certain places and didn’t move. Years later, Bernie and Leah would meet the woman who grew up in this house. Yes, the woman would say. It was always this way.

The dining room’s oval table and chairs were mismatched, but not in a fun way; some were square and made of blond wood while others were dark, rounded, and ornately carved. Leftover protest signs made of cardboard and sharpie had been hung on the walls with push pins or placed in the windowsills—this pussy grabs back and black lives matter with a sharp fist made of lines; trans is beautiful.

Have a seat, Leah said. I’ll get the others.

It occurred to Bernie then that this was a house in which beauty and meaning were opposed, in which objects were only valued if they fulfilled a functional purpose or conveyed a message. The way an object acted upon the eye or any other part of the body did not matter here. On the inside of an open closet door was taped a matte pink poster of an anatomical heart, its various chambers and veins colored in green and yellow tones. This poster could have added beauty to the space or continued its beauty, but frameless and bubbling in the middle from the placement of the Scotch tape, it did not. It wasn’t that they didn’t know what was beautiful, Bernie saw, it was just that they did not care about it.

Meow meow, said a warm black and white lump of cat who appeared at Bernie’s shins and then bumped her head against Bernie’s anklebone. Bernie’s pants were slightly too short and her socks had slunk down into bunches around her ankles so the cat’s velvet fur was shockingly soft against her bare skin.

The cat lifted her small face, closed her eyes, and began to purr in Bernie’s general direction. She had one clipped ear and one regular ear and a white marking on one side of her snout like a fat letter L which gave her face the overall charming and bizarre look of the Phantom of the Opera wearing his mask. The cat turned her substantial rump on Bernie then, exposing her pink asshole—all the more prominent against her lustrous black fur—and flopped onto the floor, where she hoisted her opposite leg into the air and began to lick herself vigorously from primordial pouch to clawed back paw.

I see you met Jigger, Leah said.

There was that smile again. No teeth, but a joy all through the forehead and eyes. The three housemates, who had filed into the dining room behind Leah, all laughed.

Leah had written the ad, but it was her girlfriend, Alex, a tall white girl with flat olive-colored limbs and brown hair gathered in a small knot at the nape of her neck, who took on the role of lead questioner once all the housemates had been introduced and settled themselves and their mugs of chamomile and Lemon Zinger along the two long sides of the rickety dining table. Bernie sat alone on the table’s short side with her back to the front door, a thing that made her jumpy and paranoid. Her father believed he had been shot in the back in a past life, and this information, if it was information, had been passed down to Bernie.

Leah and Alex sat on Bernie’s left. To her right was Violet, tall and narrow with short, dyed platinum blond hair and black roots, and then Meena, in an electric-pink mesh tank top that showed off her substantial arm muscles and looking moist, as if she had just come in from the rain.

How do you feel about public education? Alex asked.

Good? Bernie replied.

Charter schools? Alex continued.

Good?

Hmm, Alex said, writing this down on a yellow legal pad.

Alex is a journalist, Leah said by way of explanation.

You say that like you aren’t a journalist too, Alex said.

I’m not, Leah said. Not really.

Right, Alex said. You’re much too complicated to be boxed in.

Exactly. Leah smiled.

Mommy and Daddy are fighting, faux whined Violet.

Leah and Alex turned and smiled at each other, and Leah patted Alex’s skinny knee.

How do you identify? asked Meena.

Like my pronouns? Bernie answered.

Yup, but also like any other words you might want us to know that describe your identities, like working class, disabled, butch, femme, witch, poly, pansexual, sapiosexual, bottom, top, boi, stud—

Jesus Meena, you can’t say stud, interjected Violet, rolling their eyes at Bernie conspiratorially.

Really? Meena said.

Really. White people and Asians should not say it because it’s a word that comes from the Black community.

Hmm, Alex said, writing this down.

I am a woman I guess, Bernie said. Actually I prefer the word girl to the word woman if I’m being honest.

Ugh preach, Meena said.

I use they/them pronouns, Violet said.

OK, Bernie said.

And I’m nonbinary but I don’t really care about pronouns, Leah said. I mean they are great, everyone should be called what they want to be called. But just for me personally.

OK, Bernie said.

What about social justice? Alex said. Approximately how many hours per week would you say you spend working to mitigate the effects of racism, sexism, transphobia, homophobia, or classism?

Or fatphobia, Leah added.

Right, Alex said. That too.

Well, when I was younger, in college maybe, Bernie said. But now I work a lot so I don’t have a lot of free time.

And you’re a photographer, Alex said.

We googled you, Leah said.

I, Violet said, did not google you.

We looked at your photos of the river, Alex said.

Ancient history, Bernie said.

They were interesting, Alex said. Not a lot of people in them. A bit cold maybe. Almost clinical? Like for an architecture magazine maybe? As if they were old or from the past?

Alex, Leah said.

It’s not a bad thing, Alex continued. I just mean that they don’t look like they’re from today. They don’t look modern.

They’re timeless, Leah said. As in, they could be from any time. I liked them a lot and I have to look at a lot of photographs for my work. That one of the little house with the confederate flag mowed into the lawn but kind of faded and that big bird in the tree? It felt like it was about the political statement the flag was making and also not about it at all, just a photo of a house in a beautiful place with a strange-looking bird. It felt like it was trying to zoom out on that house and put it in a context, in a broader place, wherever that place was.

Central Pennsylvania, Bernie said. Where I’m from.

Well I liked that one, Alex said. That one had a message at least. A takeaway.

Violet looked up from their phone which they had slid out of their thigh pocket.

Leah knows things, they said to Bernie. About art.

Not really, Leah said. I’m getting my PhD in media studies, I won’t bore you with the details. But for extra money and because I’m interested in it, I also work for the city weekly paper. Mostly I just fact-check but I do a few reviews of shows now and then, when they let me, and some other short things. Mostly it’s a lot of reading press releases and double-checking the spellings of people’s names.

Violet’s attention was back on their phone now, their thumb swiping powerfully.

Volunteering? Alex continued. Principled consumption? Ethical giving? Reparations?

I like animals, Bernie said. I used to work at a shelter. When I was in high school.

Oh that counts, Meena said.

Does it? Alex said.

I think so, Leah said.

This is where we keep the cups, Alex said. This is where we keep the beans, the rice, the tofu, the cheddar cheese, the apples, the tubs of peanut butter, the compost, the plastic bags, though we try to use as few as possible, the mouse traps—

—I know it’s terrible, Meena cut in, but we came to a group agreement to use them last year after that mouse on Leah’s toothbrush.

Violet leaned their hip against the counter and made faces at Bernie as Alex gestured to each item, each face a little different and a little mean.

The kitchen staircase to the second floor—once used by servants! Alex informed Bernie as they climbed it, Leah, Meena, and Violet in tow—ended at a hallway with a door on its left.

Best light of anywhere in the house, Leah said.

The room was nearly round on two sides and divided into many small walls, but Leah hadn’t lied. It did get good light, south facing and strong. Three large windows made a bay that looked out over the back garden—a barren slab of cement but for a few brown vines, two white plastic chairs, and a string of globe lights missing several bulbs. A built-in wood armoire adorned with curlicues separated two small closets. Gone was the haphazard feel of downstairs. Empty, just wood and bones, this room was classical—a classic.

Bernie could imagine herself living against this background. The room felt right, like the right place to change her life. She imagined that she would be enormously productive while living in this room, taking photographs on the streets of Philadelphia and then coming back here, tired and emptied out, so the room could fill her up again.

I’m next door, Leah said, coming in and gesturing to the closed door that had once connected the two rooms but which was now covered with a sheet of Styrofoam insulation coated in a silver material, roughly cut.

Our old housemate was a fanatic about noise, Leah said. Not that it helps much, unfortunately.

Here, Leah said. See it from my side.

They moved into the hallway and then into the small room across the stairway: Leah’s room. It was painted a warm white and a thick linen curtain fell across the lone window. Her bed was crammed into the corner—small, possibly a twin, and brass, resembling a doll’s bed that Bernie had circled many times as a child in an expensive doll accoutrements magazine. Leah’s pillows were a burnt-orange color that matched the edge of the turned-back flat sheet. The comforter was plush and clean white except for the snoozing black half-moon Jigger made in its center. Jigger opened her eyes and raised her head up, annoyed.

Leah’s bedroom smelled like something, like weed but lighter and sweeter. Sage, maybe. On the left wall facing the bed was a pleasing arrangement of framed drawings, prints, and photographs, including a narrow vertically hung broadside of a poem printed in pretty serif lettering on thick deckle-edged paper.

America, the poem began. By Leah McCausland.

Oh, Leah said, don’t read that.

Violet leaned through Leah’s doorway.

I’m down the hall in what used to be the front parlor, Violet said. We three would share the bathroom on this floor. Meena’s room is at the top of the stairs, the only one with roof access.

I grow tomatoes, Meena said. And there’s a kitchen on our floor too, but no one uses it.

The whole group, Bernie included, moved into the bathroom which was windowless and strangely large. Hairs dotted the porcelain around the sink knobs and globs of toothpaste had collected on the mirror. Somewhere along the tour, Alex had taken her hair down, but she moved now to put it up again, winding a stretched-out elastic around and around a thin fistful of hair until it formed its nub again.

And Alex is upstairs in the front over Violet, Leah said.

Lucky me, Violet said, making accusatory eyes at Alex and Leah. Praise be for noise-canceling headphones.

Oh come on, Leah said, bumping Violet’s shoulder with hers. We don’t do anything you haven’t done a thousand times louder and much later at night with Lucy Vincent and, shall we say, some others?

Violet smiled widely and flicked their eyes side to side like, guilty.

How long have you two been together? Bernie asked.

Almost exactly three years, Violet answered for Alex and Leah. It was winter of senior year. I’ll never forget it because we had to have a four-hour dorm meeting about how your dating would affect the “broader social dynamic” and I nearly died of hunger and boredom. But I couldn’t leave because it was snowing.

It was not that long, Leah said.

It was that long, Meena said, which shut everyone up.

Bernie and Leah stood in the front doorway again, back in their original positions—Bernie on the porch and Leah in the vestibule.

So you let us know and we’ll do the same, Leah said.

Bernie wondered about Leah then, this person who was on the one hand so like everyone else and on the other not at all. It felt good to wonder about someone, a thing that had not happened to Bernie in a long time.

I’ll take the room, Bernie said. I mean, if you’ll take me.

Leah smiled. You have my vote.

What does it feel like, standing in the moments that will mark your life? What Bernie felt was unclear. There was maybe a certain something, a certain spice of change. This day was different, had been brought about differently—not as a result of the actions of others, but by things she herself had done.

Meow meow, said Jigger, who had escaped the house and was now rubbing against Bernie’s shin.

Oh no! Leah cried.

Bernie scooped Jigger up in her arms and was shocked by the cat’s lightness; she was just bones and fluff.

Give her here, Leah said, and Bernie did, holding the cat out to Leah like a baby.

Bernie had a feeling then. It was a feeling like don’t go, even though she was the one leaving.

For Esquire, I wrote about how ideas of queer morality and the fear of being a "bad queer" are changing contemporary American fiction.

Housemates was recommended by Vulture. Hometown mag The Philadelphia Citizen put up this blushy profile of me and some exciting changes happening at Philly’s nonprofit home for writers, Blue Stoop.

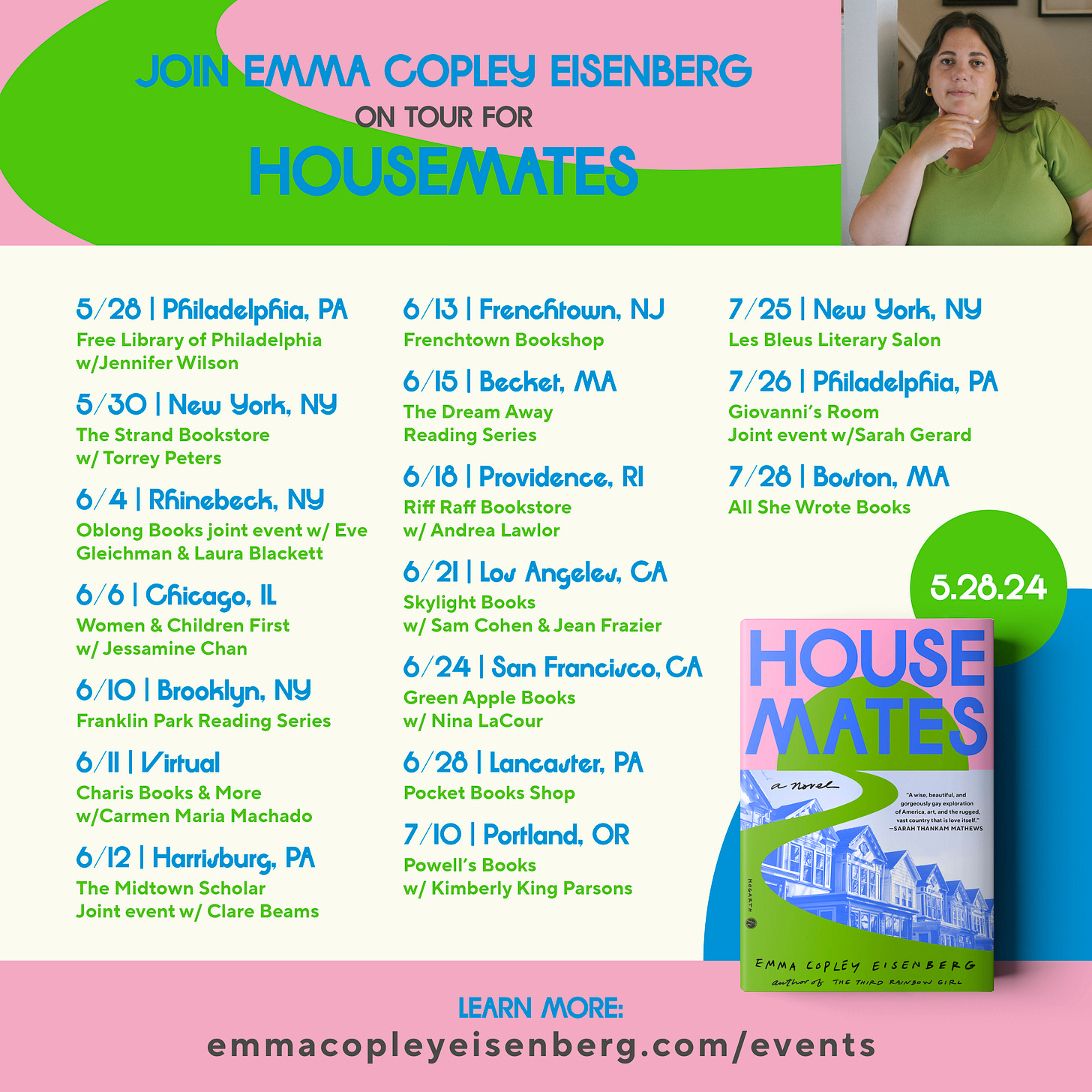

Would love to see your face! Come hang at one of these events.

I swung for the fences with this book. I gave it everything I had.

<3

Emma

Just finished. (listened: Marin Ireland was great.) Loved it thoroughly. Am about twice as old as Leah and Bernie, which sometimes is a barrier in fiction for me. But not here. The narrator is so generous--even with Dunn, who, like most people, is not summarizable as just plain bad. He's not plain-- and the insights felt so true. Plus I liked the unpredictability of how it was going to move. Speaking of moving (though to stay put) I've just moved to Philadelphia, and know little of it (I live in Graduate Hospital, in an ugly income-restricted building with glorious windows.) So this also functioned as a lovely introduction. (I have wandered Leah and Bernie's corner of West Philly, on a native Philadelphian's recommendation. Very endearing, in its ramshackle way.) Anyway, thank you for the heartening novel.

It’s September and I got the book for my birthday this month and just finished it— OMG I loved it!!! In soooo many ways!!!! Thank you thank you for my book of the year, of the 2020’s!!!! Super great….the last chapter had me weeping - I can’t quite express my self , just wanted to subscribe to your substack and tell you Thank you!!! 🙏🏽 💛🪷from my heart!