If there are, as Zora Neale Hurston famously wrote “years that ask questions and years that answer,” this has been a year that answers. My dad has been ill and my first real professor gig has come to an end and I’m at a residency in Maine working on the last revision of my first novel and all of these things have been clarifying for me. Clarifying about what I want to write and what I want to read and who I want to be. Enough with the running myself ragged over things that I don’t really want and that don’t really matter. Enough with the hoping that systems not set up to love me back will love me back. Enough with the bullshit.

I feel clear that I want my novel to have sincere ambition—to try to do something new and say something risky—even if it doesn’t fully succeed. And that I want it to have sincere emotion—characters who are raw and unguarded and try things and feel big feelings. I want the book to create an emotional experience for my reader that feels more like being human than reading about being human.

I was talking with a couple writer friends about the books we remember from childhood and that we re-read. Do we go to them because they have sharp twists of plot? No. In fact, I couldn’t tell you what many of the books I love and re-read often are about. We go back because of the feeling they create in us. No thoughts, just vibes.

Lately, it seems to me, a lot of fiction is being published that is droll and cruel and lacks sincere human emotion. These books mock and flirt and wink and avoid any real feeling, as if vulnerability itself was disgusting. I’m not quite sure how this happened, why it has become that one of the things that the contemporary publishing landscape rewards is lack of affective ambition, a kind of hedging of emotional bets. The characters are numb and the stakes are low.

I’ve noticed this in particular in a crop of recent novels that contain queer sex or relationships but actually seem to have been written for straight people. These books seem to be writing within a presumption that the struggle for queer liberation and other social movements is over, and in so presuming, don’t bother to reckon with the internalized homophobia and fatphobia and racism they reinforce or the ways in which the characters themselves are still stuck and afraid and still projecting that fear onto others by the end of the book. I’m writing a piece about two recent novels that I feel really exemplify this trend for the summer issue of Lux Magazine.

This doesn’t mean that I want my novel to be a festival of sadness. No! I hope it contains rage and guilt and shame and joy and I hope it is at least a little bit funny, and I have put in quite a few of what I, at least, consider jokes. Real feeling to me absolutely includes humor, and my favorite practitioners of funny writing (Grace Paley, Samantha Irby, George Saunders, Laurie Colwin, Lore Segal, Miranda July) are writers whose work opens you up with a joke so your belly is exposed and then jabs you right after with the inevitable sadness of being alive. (Credit for this insight goes to the wonderful writer Courtney Sender, whose book is also recommended below).

How will I make sure, as I revise and finish, that my novel does all these things though? It’s hard. Garth Greenwell has been teaching a class through The Shipman Agency just about Alexander Chee’s (beautiful, very queer, very big feelings) novel Edinburgh, and apparently when asked how he knows when a novel is done, Chee said, “think about the images left in your head that you want in the story; think about the issues left unresolved. Make a list. Once you have checked those off, your draft is done.”

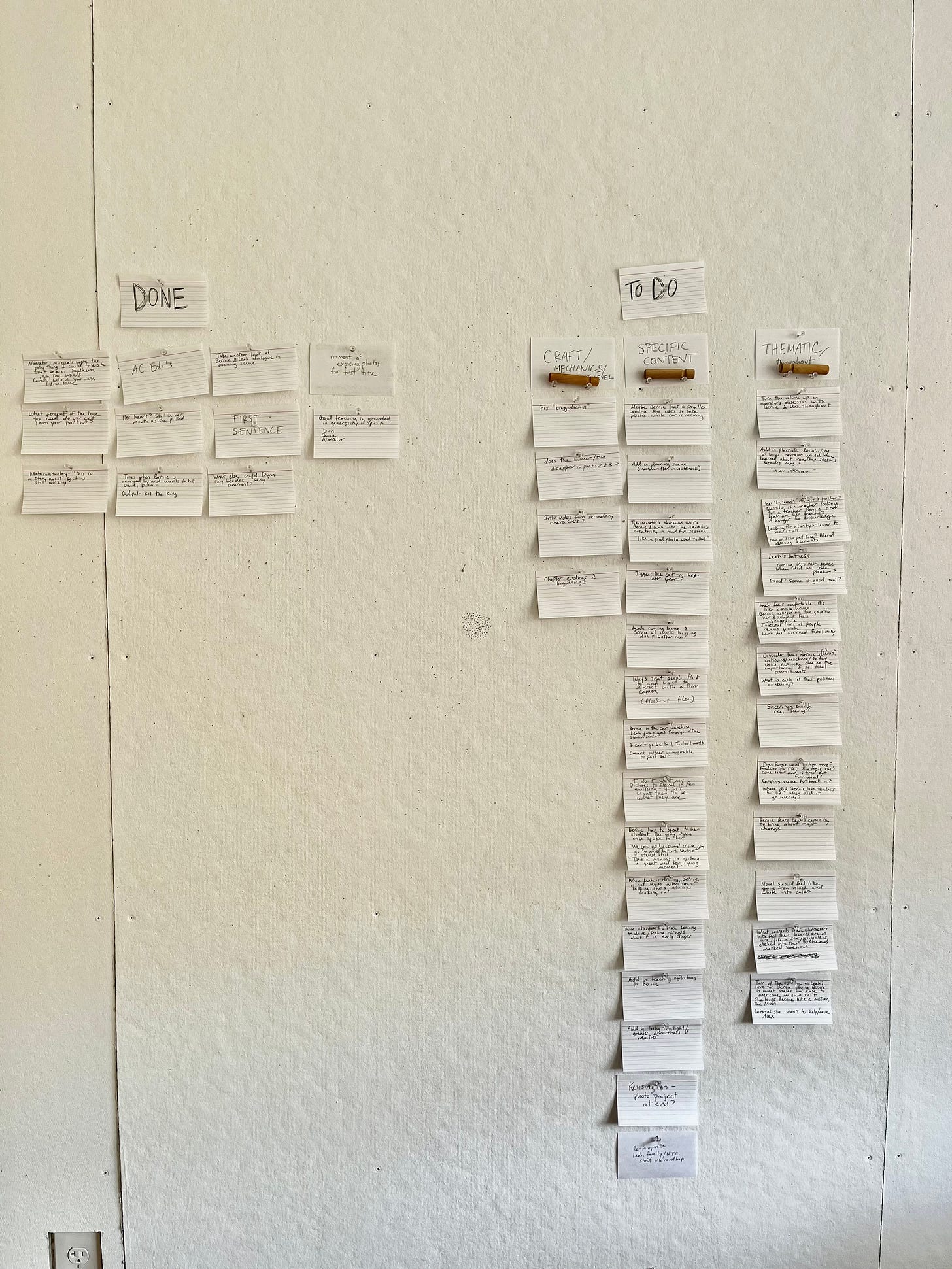

So here’s a snapshot of my revision process for the final draft of my novel, taking Chee’s advice and adding my own systems. I’ve been taking advantage of this big cork board wall at the residency where I’m at to list all my intended revisions for the final draft. I put down, each on separate index cards, all the things I want to add or change based on the conversations I’ve had about it with my editor, some early readers, and my own thoughts too of course, collected in the notes app on my phone as I’ve walked around and taught writing over the past five months or so since I turned in the previous draft. Then I sort the index cards into three categories: craft/mechanical/sentence level work (things like paying attention to the ends and beginnings of chapters, experimenting with a new kind of sentence, or fixing the opening line) specific content (scenes, images or moments I want to add or adjust), and finally thematic concerns I want to hold throughout the revision (ways of seeing the central relationship that someone opened up for me, thoughts on the narrator’s stake in the telling, etc).

It looks like this:

So when I’ve addressed the thing in the revision, I move the notecard over to the “done” area.

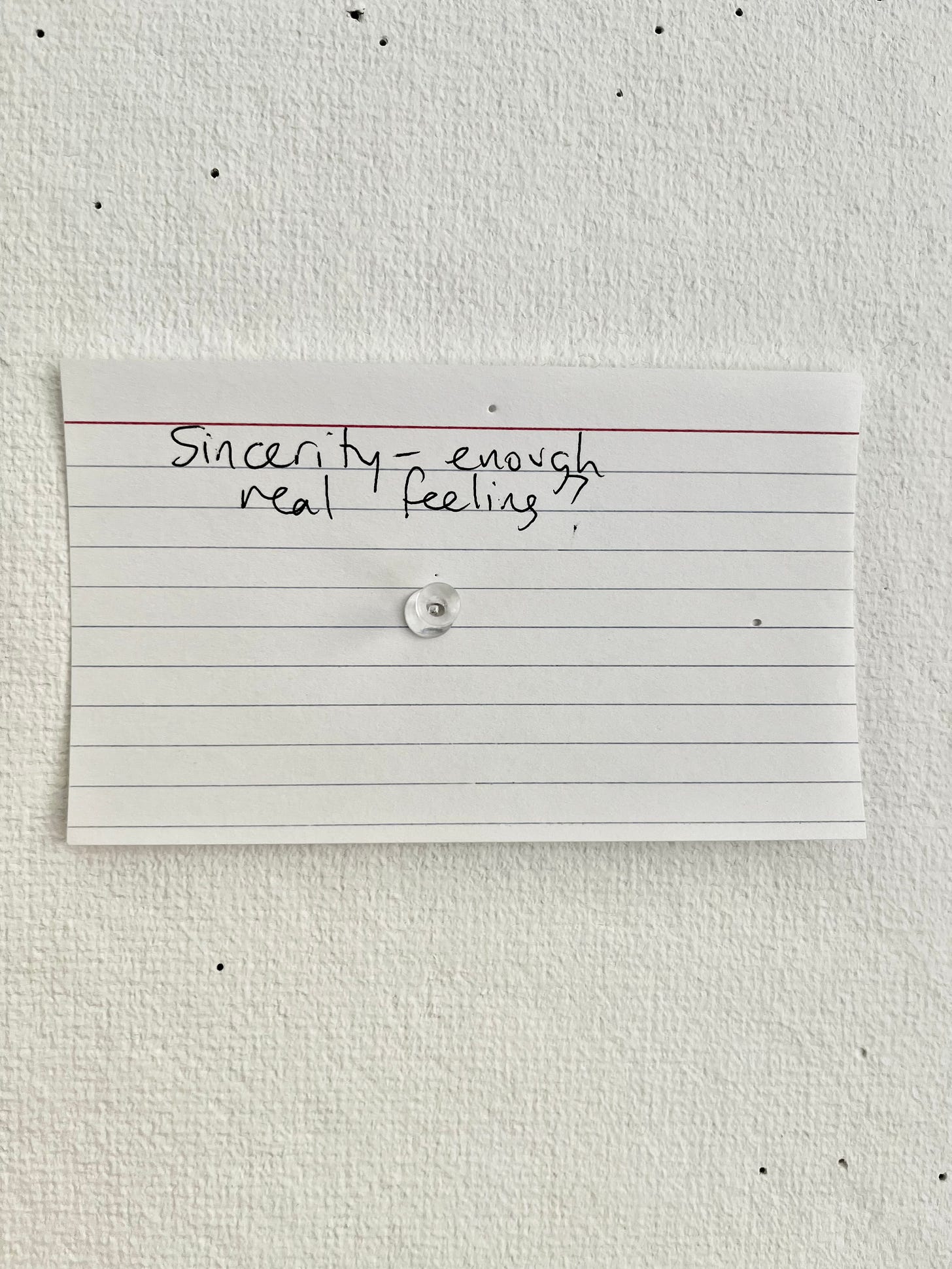

I few days ago as I was thinking about writing this, I realized that I was unsure if my novel did the very thing I’m being cranky about other people’s novels not doing. So I decided to add a notecard into the “thematic” category so I make sure to bring attention to this specific concern as I finish.

I’ll report back on what I find out, though I suspect it will be laughable because I have, and my characters have always had, SO MANY FEELINGS!!

I also feel clear that I want to be someone who participates in the marketplace of books in as generous and transparent a way as possible, who is involved in making the industry more human not less, and that I want to work only with other writers and professionals who do the same. And that I want to give my time to reading, more than not, books that allow their characters real feelings and offer a certain generosity of spirit.

A very non-comprehensive list of books I’ve read and loved recently that DO contain big, sincere, risky, human emotions and that hold nothing back:

The Hero of This Book by Elizabeth McCracken. This was a balm for me this past month as I was in and out of health care facilities with my dad. A book that renders, with so much precise tenderness and generous distance, the experience of losing a parent who you love and who has shaped you physically, emotionally, and intellectually.

All This Could Be Different by Sarah Thankam Matthews. As the title suggests, this is a novel about how the world is and how it might be, if we let ourselves dream a different kind of future. It’s also a coming of age novel about a young college graduate trying to find her place in work, in queerness, in America, and in community.

The Seas by Samantha Hunt. This is a gorgeous, strange, sparse book that will swallow you up with the force of its urgency. It’s about the ocean, being in love with someone who doesn’t love you back, and ambiguous loss—the kind of loss that happens when someone is gone but not dead or gone little by little.

Terrace Story by Hilary Leichter (coming this August, pre-order!). From the seed of Leichter’s incredible short story for Harpers about a struggling couple who finds a portal to a magical terrace in their closet and unspooling from there in completely original and indescribable ways to think about love, grief, parenthood, and longing, this is an unmissable and terribly funny book.

In Other Lifetimes All I’ve Lost Comes Back to Me by Courtney Sender. I loved this short story collection so much I had to interview Sender for Electric Literature, out later this month. The characters in these stories long so fiercely for love and meaning that they can conjure a convergence of ex-lovers, talk to God, re-vision the Holocaust and more. It’s a hilarious, tragic, very Jewy book of millennial feminist rage.

Trust Exercise by Susan Choi. I bought this book when it came out (and won the National Book Award) several years ago but stumbled perhaps three times on its long opening section, unable to dive in. It was only when I decided to try it on audio that I understood it. And loved it. This is a book about the very things I was trying to write about above —artistic ambition, feeling vs. numbness, privilege and access and power. The cruelty and meanness of the narrator of part 1 is cracked open in part 2 in a way I’ve never seen anyone do before.

Tomorrow and Tomorrow and Tomorrow by Gabrielle Zevin. Zevin’s strength for me is not in the styling of her prose, that isn’t what made me love this book, which I also listened to on audio. It’s her ambition, the boldness and brashness of her vision. She makes at least seventeen different worlds real in this book and her characters love and scream and die and dream up video games with abandon.

One last thing I’ve gotten clear on this season: I’m no longer gonna sit there silently when people say messed up things about fat people, or talk about their diets, calorie counts, weight loss, juice cleanses, how they’ve been “bad” today with food, or need to exercise “so that” they can eat. I practiced this just the other day at the artist residency where I am, asking the resident in question if she wouldn’t mind chilling out on all that talk around me. She said sure. It was scary and brave and vulnerable to say that out loud. And it was fine.

Yours, in feelings,

Emma

I like these lines in the sand very much. As for something working or not working, there’s nobility in the attempt. This is from a NY Times review of the new film “The Master Gardener:” It shouldn’t work and, even after seeing it twice, I don’t think that it entirely does, which only makes it more fascinating and strengthens its power.

Thank you for writing this Emma. I feel the same--about needing sincerity now. I've always needed it in poetry, and I think I've always wanted it in fiction, but I spent a long time trying to read things that felt exactly how you describe--heartless/hollow/mocking because they were lauded as really good books. Since children and since grief that stuff has only felt more cruel and disheartening. I'm grateful for the permission in this essay to love books for their deep and resonant vibes. Love you always.