August, it seems, is for the body. I went to the beach and felt sensations. It was very nice. And yet, even there, I still did not feel good in my body, shall we say. I did not feel “at home.” As a friend of mine recently put it, “feeling bad in my body still hurts.” Fuck, yeah.

Do you ever feel that there is some zone of happy living that is just out of reach for you and that maybe it has to do with your body? Some sense that something is waiting just below the surface to be unearthed and that you can’t get at it with your mind?

I have been having this sense nearly every day for circa two years, but all of a sudden since things have quieted down with the book tour for my second book and first novel, Housemates, the feeling has reached a roar. I have the strong sense that I have gone as far towards joy as thinking can take me and that the next phase lives, unfortunately for me, somewhere south of my head.

I say unfortunately because for me, my body has often been a site of un-fortune. I’ve written here about growing up in a deeply food dysfunctional and fatphobic household and I’ve written here about some of the things I’ve done to try to heal from it (intuitive eating, an eating disorder focused therapist, a fat positivity support group, an embodied healing group).

It’s weird too because the feedback I’ve gotten most consistently from people who read Housemates and liked it is that it is very bodily, that its characters are deeply embodied. “MFA programs tend to deprioritize the body, and that never really worked for me,” goes an interview I was lucky enough to do with critic Ilana Masad for the Los Angeles Review of Books. “POV is body, plot is body, structure is body. You can’t strip away the body from any of these craft elements—or at least I can’t. The bodies of my characters are where a lot of the impulse for fiction comes from—what they desire, what they fear, how they experience being a human person.” I said all these things. I believe them.

And yet, I don’t regularly pay anyone to touch my body. I belong to no sports teams, no gym, no dance studio. I don’t take any movement classes. I go to therapy every week (I would estimate that solidly 30% of the non-scenes in Housemates are verbatim insights from therapy sessions) but I do that while sitting at my desk or on my office napping couch.

The other week though, I was sitting around a stone table at the Tin House summer workshop with some of the other faculty and I asked them a question — “how well are you?” I wanted to know what they, all these writers whose minds I respect so much, do with their bodies. They all had answers. They meditated or did yoga or routinely got acupuncture treatment or regular massage or they danced. In other words, they took care. They enjoyed physical things. They didn’t have it all figured out (who does?) but they were making regular attempts and experiencing benefits, in their lives and in their writing, from being on speaking terms with their bodies. When had I fallen so bodily behind my contemporaries?

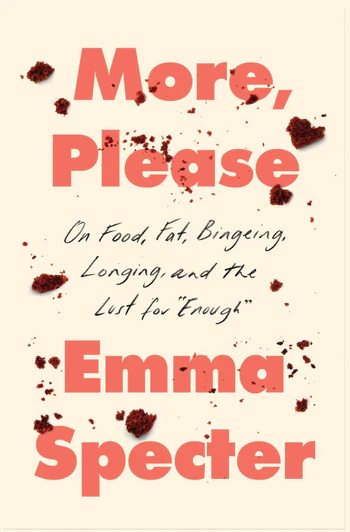

This month, I tried to begin to answer this question by reading Emma Specter’s new reported memoir More Please: On Food, Fat, Bingeing, Longing, and the Lust for Enough, which just came out last month from Harper Collins as has been getting raves everywhere. Being me, even after I was done, I still had many questions. So here is a conversation I had with Emma S about all this and more that we will now share with you.

Emma Copley Eisenberg:

Welcome Emma Specter! Your book is a book I needed when I was younger, a plump little girl trying to hate her body less, and it’s a book I needed now, as a fat adult literary writer trying to make good art and live well in a fatphobic world. So thank you for that!

First question: it’s August, I’m writing this to you from the beach where I sit in a swimsuit. What has this summer been like in your body?

Emma Specter:

I love this question! The existence of hot fat swimwear has done a lot for my summer, but rather than just focusing on a few sartorial high points (like wearing my Samantha Pleet bikini to a queer pool party or my Mara Hoffman rash-guard to the beach in Malibu), I’m trying to make mental room for all the experiences of being in my body this travel-centric summer: the dazzling joy of plunging myself into a creek in Hood River, Oregon or the quiet pride I feel when I finish a Pilates class, yes, but also the stress of not knowing if a Spirit flight seatbelt will fit me without a seatbelt extender (it won’t) or the physical discomfort of racing through the airport to catch a delayed-then-undelayed flight in the wrong shoes on a day when, of course, I’ve forgotten to put on my anti-chub-rub cream. There’s value in all of it, as they say, and while there are things I would alter (specifically, I would love for my right knee to stop popping every time I get up quickly), I’ve never been more grateful than this summer for all the stuff my body can do. What has YOUR experience of being in your body this summer been like, Emma?

ECE: Oof all of this resonates so hard. Something I’ve been thinking a lot about is how most of the feedback from my body I’m attuned to is negative. Like I only seem to notice when my body is in pain or feels out of whack or feels too large to fit. I think for whatever reason – the stress of putting out a book? Engaging more directly with fatphobia in my writing? – I am feeling a lot more bummed out about my body lately even though intellectually I’ve never had more resources to talk about fatphobia or more fat community. Your book tackles this contradiction, which is part of why I loved it so much. I wonder what you would say to all of the folks out there who know it’s ok to have a body of any size but are still hurting?

ES: This is real as hell! I think we expect our feelings about our bodies to be linear, i.e. “I’ve done so much of the work of unpacking fatphobia in my life, thus my feelings about said fatphobia and about living in a fat body should only get better as time goes on,” and I’m pleased to say that sometimes that’s the case, but a lot of the time…listen, “when you’re getting better, it’s a jagged line,” as Jenny Lewis says. Sometimes your body hurts and your heart hurts from knowing there are a lot of people out there who would instinctively blame you for the pain you’re experiencing, and you are not bad or wrong or somehow an enemy to your body for sitting with that pain! I think the most beautiful thing we can do as fat people is just stop to take care of ourselves (make tea, take a restorative yoga class, smoke a joint in the bath, nap on and off all day, organize your freezer if that feels like self-care to you) when the world is constantly telling us we don’t deserve to.

ECE: Totally. The pain is unavoidable and it does us no good to try to block it out. You address this a little bit in More Please, but I’m wondering what you were taught as a kid about the connection between the mind/intellect and the body? Like do they need each other? Hate each other? And, related, how did you go about trying to translate the experience of having a body into the written document that became this book?

ES: I recently asked my dad–a very fit and health-oriented person whose idea of a relaxing Sunday is a 30-mile bike ride–about this, and he basically told me that he didn’t force me to do outdoor stuff when I was growing up because you can’t make kids exercise, it has to be their own decision (and ultimately, they’ll spend all their energy fighting whatever you try to insist they do instead of actually doing said thing.) I think this is a deeply wise approach, and at the same time, I wish I’d discovered the forms of exercise that I now love–swimming, Pilates, slow walks to go get a latte–earlier in my life, just so I could have had a few extra tools in my emotional-regulation toolbox. I’m 31 and just learning that sometimes exercise can make your brain feel good–wild stuff!--but I also think that’s just how my capital-J Journey needed to shake out, and honestly, I’m so grateful that my parents were pretty hands-off about what I ate and how I moved my body, especially when I was a tween; your brain is so primed to remember negative self-image stuff from that era, and I think my parents’ policy of “There’s a reasonably healthy breakfast on the table, but if you want to get a bagel on the way to the subway with your own money, we can’t stop you” was a lot less destructive than force-feeding me or forbidding certain food items. Do I feel like I figured out a lot about the mind-body connection on my own, later in life? Sure, but better late than never, right?

As for how I tried to translate the experience of having a body into this book….such a good question! This is a corny answer, but I do think that over the course of writing the book, I became way more grateful for the sheer fact of my body–its abilities, its potential to learn and improve, its relative freedom in a world full of increasing oppression and horror–and I really hope that gratitude shines through. I also really didn’t want to shy away from the physical discomfort and self-disgust that can come with bingeing, even though my instinct is still to lie about it or sanitize it; ultimately, having a body is a terrible gift and a gorgeous burden, and I never want to forget that.

ECE: Not corny at all. Just gorgeous. Last q: what surprised you most when writing More Please? What insights about having a body or the nature of eating disorders came to you not from the outside intellect, but just from inside the act of writing?

ES: Hmm. A thinker! This is more an insight about me as a person than me as a disordered eater, but then again, I guess they’re arguably connected. For most of my life, I didn’t have a good sense of myself as someone who “did the work”; I was ass at K-12 school, I didn’t try hard academically even when I found myself at a college I actually liked and mostly just had to write essays for, and along the way, I formed an impression of myself as a little bit of…well, a slacker. Writing this book–like, the physical process of sitting down on my broken bisexual-green couch almost every night for the year I lived in Austin and doing the actual sentence-by-sentence labor of turning a proposal into a fleshed-out book–reminded me that I am actually capable of putting a lot of work into something, and that it’s worth challenging old narratives about myself (I haven’t been a messy, forgetful fourth-grader composing a slapdash poem about frogs for Earth Science in about two decades, so why am I still reverting to that mindset when it comes time to evaluate my work ethic?)

Actually, I do think this is kind of connected to bingeing, insofar as you are what you do, to a certain extent; I’m a binge eater, but I’m also a writer, and I’m learning to let myself be surprised and pleased by the beauty that can occur when I fully sit inside both of those identities.

Toppings

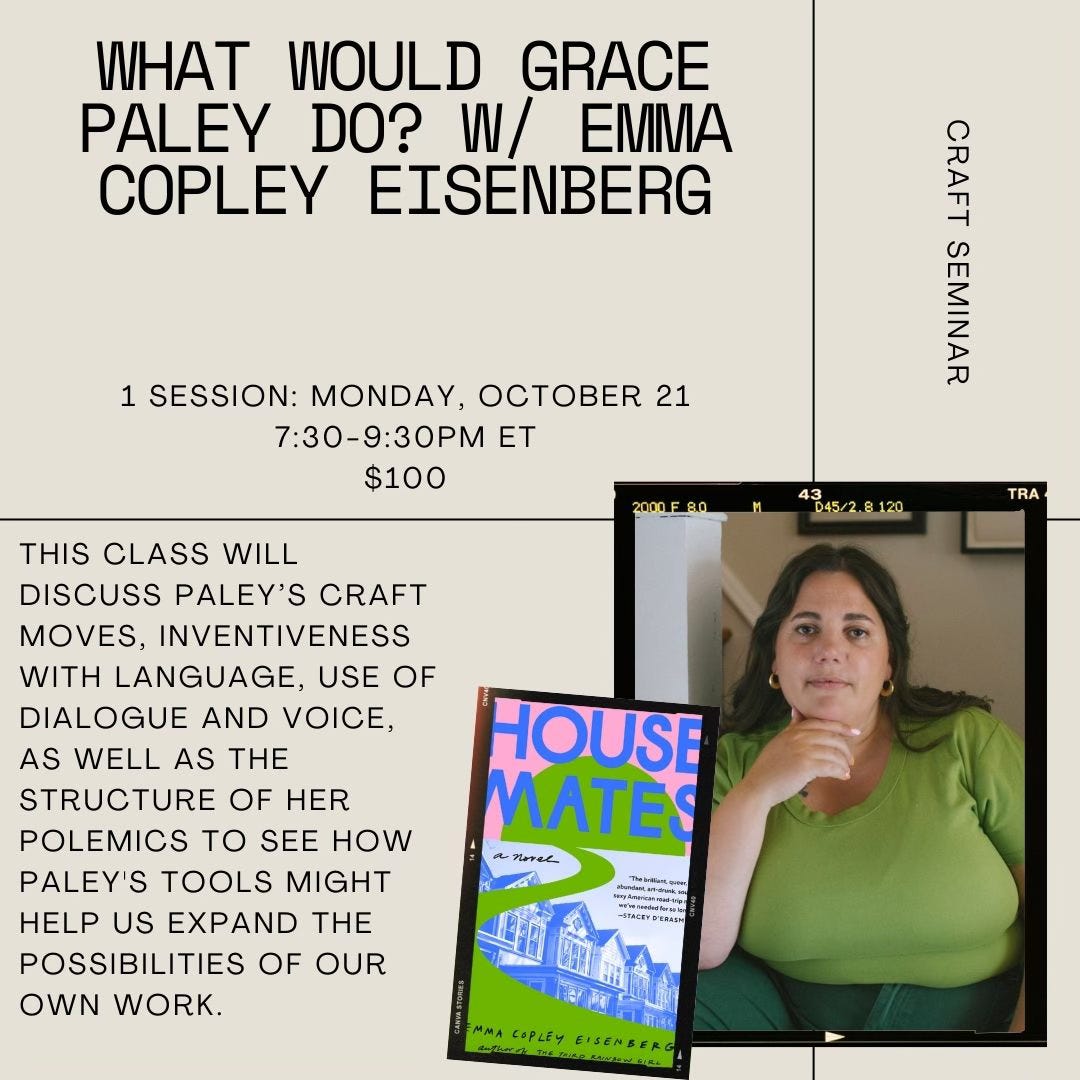

I’m teaching two classes this fall open to the public; the first is October 21st about the work of Grace Paley. Called "one of the truly original voices of American fiction in the later twentieth century" by The New Yorker, Grace Paley (1922-2007) is at once a giant in the literary canon and gigantically forgotten. But without Paley there would be no George Saunders and perhaps no ZZ Packer or T Kira Madden; Paley's humor and innovative dialogue and knack for compression rewired American letters. Further, Paley was a committed activist against apartheid, Zionism, and fascism. What can we learn from Paley in 2024? How is the craft of dialogue, character, and scene profoundly connected to the work of justice? The class lasts two hours and costs $100 and you can register here.

The second class will be on November 2nd through Tin House and it’s on a topic YET TO BE DETERMINED. What do you really want to take a class about? What do you wish someone (me?) would offer but they never have? How to begin writing a novel? Where do ideas come from? What makes writing funny? Please tell me below in the comments if you have an idea for a class you’d love to see me offer.

I taught a 90-minute craft talk called “Where Are All the Fat People in Fiction?” about how fatphobia shows up in contemporary American fiction and about novels that depict larger bodies in more liberatory ways. It was recorded and is on sale through August 30 for just $15 through Blue Stoop, a local Philly nonprofit where I am on the board. All proceeds go to sustaining Philly’s vibrant and diverse literary community.

For the first time in moons, I read books! At the beach. I read Alexandra Tanner’s Worry and Rufi Thorpe’s Margo’s Got Money Troubles and Yasmin Zaher’s The Coin, and re-read Sophie’s Choice, which I do every summer, and which is actually more about a horny group house in Brooklyn than it is about the Holocaust. Unfortunately, I found The Coin to fit into a trend I’ve written about before called “The Unhinged Bisexual Novel” a major feature of which is an antiheroine who is anti-fat. Alas! Perhaps I will write a separate Substack about it.

Book Scoop

People who write about books are so smart and cool. They deserve all the flowers. Here are just a few of my favorite recent pieces of Housemates coverage: Jordan Kisner for her Thresholds Podcast (the Ottessa Moshfegh to Grace Paley spectrum of fiction!), Kate Tuttle for The Boston Globe (the historical queers that inspired Housemates!), Ilana Masad for LARB (embodiment as plot!), Elizabeth Endicott for Electric Lit (the headline makes me blush — “Emma Copley Eisenberg’s ‘Housemates’ Is a Lone Departure From the Fatphobic Literary Hellscape”!) , Shy Watson for the Creative Independent (class and money in fiction!), and Jessica Ferri for the

(the erotics of making art with others!).I’m going back on the road! (face smiling/sweating emoji!). If you’re in Baltimore, DC, Western Mass, Hudson Valley, NYC, Miami, or PA environs, I’d love to see you. Full deets of all events are on my website.

<3 <3 <3

Emma

If you liked this newsletter, feel free to share it with other people, to subscribe to this newsletter as a free or paid supporter, or check out my novel Housemates.

It’s interesting that you feel so behind, and Emma also expresses that she wished she had found certain body practices sooner as well. Maybe this behindness you feel is just the signal that you’ve reached a time in your life where it would feel good to explore, and you simply weren’t ready until now. I'm also wondering at what stage in their life were the other people sitting around that table. Maybe they didn't get to those embodied activities any earlier. I say this as a 47-year-old who only found Pilates and short walks two years ago and hated every form of "movement" all of my life until then.

Wow thank you for coming to Western Mass!! Adding this to the calendar for chilly November <3